When Nicolás Maduro was removed from power by the United States, many in Washington expected the U.S. to rally behind Venezuela’s most prominent opposition leader.

Instead, the Trump administration moved to engage a longtime Maduro loyalist, signaling a transition strategy driven less by democratic symbolism than by concerns over stability on the ground.

The approach sidelined María Corina Machado, the opposition leader who claims the strongest popular mandate and international profile, while elevating Delcy Rodríguez, Maduro’s vice president and a central figure in the outgoing regime.

Administration officials and outside analysts say the shift reflects a calculated effort to avoid a power vacuum and maintain control during a fragile transition, even as it complicates Washington’s longstanding support for Venezuela’s democratic opposition.

And President Donald Trump is betting Rodríguez now lives in fear of what might happen to her if she defies the U.S.

Trump, describing his phone call with Rodríguez, said she offered: ‘We’ll do whatever you need.’

‘I think she was quite gracious,’ he said.

But in a separate interview with The Atlantic he warned: ‘If she doesn’t do what’s right, she is going to pay a very big price, probably bigger than Maduro.’

Following Maduro’s removal, Delcy Rodríguez was sworn in as Venezuela’s interim president after the Supreme Court ruled she should assume power in his absence.

Under Venezuela’s constitution, the vice president can serve on an interim basis while the country determines whether and when new elections will be held. While the constitution generally calls for elections within 30 days if a president is permanently unable to serve, authorities have so far described Maduro’s removal as temporary, allowing Rodríguez to remain in office as the timeline for a political transition is debated.

A classified CIA intelligence assessment examined who would be best positioned to lead a temporary government in Caracas, Venezuela, and maintain short-term stability, a source familiar with the intelligence told Fox News Digital. The report, requested by senior policymakers and presented to Trump, aimed to offer the president ‘comprehensive and objective analysis’ on possible scenarios after Maduro’s capture.

A source familiar with the assessment told Fox News Digital that the assessment attempted to analyze the domestic situation in Venezuela, but did not describe how Maduro could lose power or advocate for his removal.

Trump senior policymakers requested the assessment — specifically one that addressed who would be best able to stabilize Venezuela ‘immediately’ following a Maduro removal.

‘There was sentiment among senior officials that Machado lacked the necessary support in Venezuela if Maduro was to be removed,’ the source familiar told Fox News Digital.

One of the reasons for that, the source told Fox News Digital, was because Machado was not in Venezuela, though she has vowed to return.

The report found Rodríguez would be best positioned to lead a temporary government in Caracas, Venezuela, and Gonzalez and Machado would struggle to gain support from security services.

While Machado has been widely embraced by Western governments and democracy advocates, U.S. officials and analysts say that support has not translated into leverage over Venezuela’s military or security services.

Trump’s skepticism also has been shaped by frustration from his first term, when international backing and opposition momentum failed to produce a transfer of power.

‘Machado has an inherent problem from the get-go,’ said Pedro Garmendia, a Venezuela expert and Washington-based geopolitical risk analyst. ‘She doesn’t control troops or hold any sort of power in Venezuela.’

At the same time, ‘Rodríguez is an ideologue,’ he said. ‘In the long term, the Trump administration might find itself having trouble reining her in.’

Trump has been more blunt in explaining why the administration has not rallied behind Machado. Speaking after the operation that removed Maduro from power, Trump questioned whether she could lead Venezuela in a transition, saying she lacked sufficient support inside the country.

‘I think it would be very tough for her to be the leader,’ Trump said. ‘She doesn’t have the support within or the respect within the country.’

A Washington Post report had claimed that Trump was upset Machado accepted this year’s Nobel Peace Prize — an award he coveted and that she dedicated to him. But the White House insisted Trump’s actions were the result of internal briefings.

‘President Trump is routinely briefed on domestic political dynamics all over the world. The President and his national security team are making realistic decisions to finally ensure Venezuela aligns with the interests of the United States, and becomes a better country for the Venezuelan people,’ said White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt.

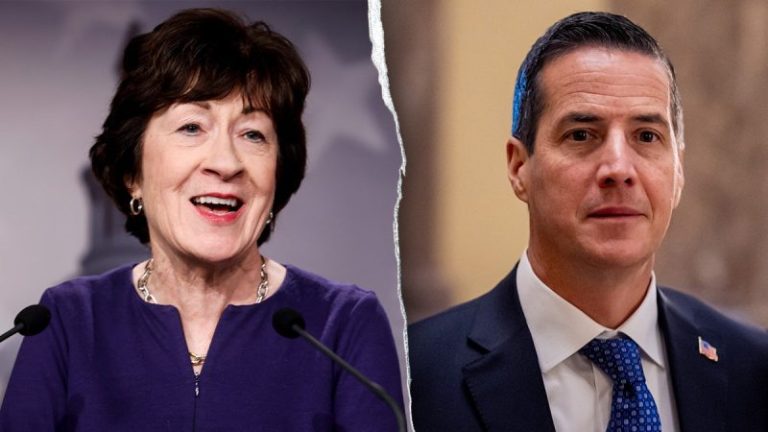

Rubio has sought to frame the decision as mission-driven rather than personal, pointing to past U.S. interventions as cautionary examples.

‘I have tremendous admiration for María Corina Machado. I have admiration for Edmundo,’ Rubio said Sunday on CBS’ ‘Face the Nation.’ ‘But there’s the mission that we are on right now. … A lot of people analyze everything that happens in foreign policy through the lens of Iraq, Libya, or Afghanistan. This is not the Middle East. This is the Western Hemisphere, and our mission here is very different.’

The administration’s caution also is shaped by a long history of U.S. intervention in Latin America, where American-backed coups and political engineering have left deep skepticism toward Washington’s motives. Installing an opposition leader immediately after a U.S. military operation, analysts warn, could revive those suspicions and undermine any transition before it begins.

‘If they were to bring María Machado and presumably Edmundo González back to the country and install them as president, it would look a lot like the United States installing a new president,’ said Eric O’Neill, a former FBI counterintelligence operative. ‘That would actually cause civil unrest.’

‘Venezuelans are proud people, and they need to elect their next president,’ O’Neill added.

But Garmendia said Rodríguez is ‘just as illegitimate as Maduro was — and probably even less popular.’

He said Rodríguez lacks the charisma and mass appeal that traditionally have sustained Venezuela’s ruling movement, and that her authority rests largely on internal bargaining and elite control rather than public support.

In the interim, locals have reports of armed gangs patrolling the streets. Venezuelan authorities have detained at least 14 journalists since Maduro’s capture, according to the union representing Venezuelan reporters.

‘There’s going to be a lot of instability in the next couple of weeks,’ Garmendia said.